Preface

I have an old and battered silver wine funnel in my possession, which belonged to my forefathers, who were all ardent fox-hunters. Many a time have I thought what tales it could tell if it could only speak, for it has, doubtless, been present at many a hunting dinner in the days of yore, when people were more particular about the condition of port than they are nowadays. The thoughts it conjures up in my mind are of a very pleasant nature, and to it is attributed the conception of this little work.

Chapter I

Mr. Goodbery is standing with his back to the fire, the tails of his well-worn red coat thrown over his arms. Above him hangs a portrait of Peter Goodbery, his father, who lived in Foxley Grange before him and hunted the Foxley Harriers to the day of his death. The present Mr. Goodbery is one of the old school, and the sporting instincts of the father have been inherited by the son. It is natural, therefore, that it should be our hero's favourite pursuit to follow the hounds.

Mr. Goodbery is a stout gentleman of comfortable means, and still more comfortable appearance. To be exact, his income is £2,500 per annum, derived chiefly from land. He troubles himself little about business matters, and has a dread of married life, as he has seen so many of his companions, jolly good fellows when single, become rather sober and thoughtful after entering the lists; consequently, he is rather apt to shy off the fair sex. Although he has been talked to by his married friends and recommended to follow suit he always thinks they are like the fox who lost his brush, and so he means to keep clear himself.

Foxley Grange is a charming place, with its many gables and picturesque windows peeping out through the ivy and wisteria. The old house dates back to early in the sixteenth century, and is built partly of brick and stone – a roomy house with an old-world air pervading it. The gardens, laid out in the Dutch style, still bear signs of their original grandeur, although they are now somewhat neglected. No doubt Court ladies have graced the walks with their presence, for the villagers speak with veneration of the quality that once resided within its hospitable portals. The shape of the beds recalls my lady's flower garden, and a broken sun-dial covered with lichen and an old stone seat bearing unmistakable signs of "anno domini" help to arouse pleasant memories of by-gone days.

On entering the house, the first thing that claims attention is a magnificent oak staircase, made so wide and strong that no doubt the architect built it with a view of allowing enterprising horsemen to ride up to bed on horse-back, which was a favourite amusement in the olden days, so 'tis said. The hall is laid with good stone flags; opposite the door is a generous fireplace, where a couple of large logs blaze on the andirons and make things cheerful at Christmas time – for our forefathers did a good deal of entertaining in their halls, where the young folk could make as much noise as they liked, without disturbing the old people over the cards and negus.

Then what cellars there are under that house! Enough room to stow away a regiment of soldiers; but put to better account than that, for our ancestors were a very independent set, and liked to be their own factors. There are innumerable cupboards, rooms and recesses, used for pickling, baking, brewing, and the storage of apples and cheeses, also a large vault-shaped room well stocked with wine, for it is a very necessary thing to have ample room for laying down port, as three-bottle men like their wine to be old and crusted. The kitchen is well worth a visit, its quaint ingle-nook and hearth giving an air of home and comfort to the house. Down the chimney hangs a series of pot hooks, where the iron saucepan is suspended that contains pot-luck for the hungry hunter. From a beam across the ceiling there dangles a row of fine hams in canvas bags, which Mrs. Stores, the housekeeper, has cured at home, for has she not the chimney where all that appertains to the mystery of bacon curing is conducted? What a comfortable old settle, too, with a high back that keeps off draughts and makes things cosy. This is the seat frequented by the gamekeeper or groom, who, after a long day with their master across country or through the turnips, may enjoy a meal there by invitation. All these things were part and parcel of country house life when agriculture was in a more prosperous state than in the present day, and landlords were able to live on rents received from their farms.

The reception rooms of the Grange are not exactly spacious, but there is plenty of room for the dispensation of English hospitality, and a charming suspicion of former times still lingers about them, recalling the days of hair powder, high heels, and ruffles. Strange tales are told of mysterious noises heard in the corridors at dead of night – the rustle of silk gowns and jingle of spurs being described as some of them. An affrighted guest, who was on a visit to the Grange for a fortnight, hearing these sounds, packed his box at break of day, vowing that important business compelled him to return to town at once. Mr. Goodbery, however, has never heard any of these noises, although he has lived in the house all his life, and he attributed them to the cold pork and pickles his friend had been eating for supper. No doubt, once in bed, Goodbery sleeps too soundly to hear anything, for a hard day's ride after hounds is conducive to peaceful slumber.

Of late years our host has been unable to walk quite as well as he could wish whilst shooting, and so has had recourse, good sportsman that he is, to a shooting cob, "for," says Goodbery, "17 stone for Shanks's pony is a good deal to carry." When shooting one day, being mounted as usual, and coming across some heavy land that lay on the side of a steep hill, he called on his fellow sportsmen to keep up in line, forgetting that he was mounted and they on foot. The poor fellows did their level best to keep the line with him, upon which he remarked, with a wicked twinkle in his eye, "I say, you fellows, this makes you huff and puff a bit, don't it? Come on, my lads, keep in line! keep in line!" But to our tale.

Mr. Goodbery is going hunting to-day. Not that this is an unusual event in his life, for he takes the field about four days a week. This morning he is expecting Oldwig, a hunting friend, to call for him on the way to covert, and on looking out of the window he sees that worthy riding up the drive on his hunter. Goodbery is blessed with a coachman who is always on the spot when wanted, and of course is there to hold the stirrup whilst the guest dismounts, should he so desire.

"Welcome," exclaims the hearty host in a joyous voice, "and let me give you something, for the weather looks somewhat threatening and you know the old maxim, 'He who would the dart of death defy, should keep the inside wet, the outside dry.'" With these words he produces two large silver tankards, bearing by their dents probable evidence that they have been used at an earlier date in settlement of some difference of opinion. These he causes to be filled with good nut-brown ale, for Goodbery believes in moderation early in the morning, and never drinks anything stronger than ale before dinner.

Oldwig remarks that they have no time to waste, and must be moving if they do not wish to be late; so wishing themselves good luck, they are soon on their way to the meet. Our hero mounts by the aid of a horse-block, for he is no feather-weight, as we have already hinted. Oldwig sometimes jocularly remarks to his friends, "What does it matter to a man like Goodbery if he weighs more than any one else in the hunt? He's got good hands and judgment, a long purse, and to my mind, his weight rather tends to steady his horses at their fences than otherwise."

As they jog along to the meet they fall in with several other sporting people, all bound in the same direction. Amongst them is Miss Richmond, mounted on a white Arab and escorted by a negro servant in a gorgeous livery and riding a similar animal.

"Good morning. Miss," says Oldwig, raising his hat. "Glad to see you are going to honour the hunt today with your presence." At which Miss Richmond smiles and says nothing,

"Might your father be coming out this morning?" ventures Goodbery.

"Yes, papa is coming; in fact, here he comes," as an old-fashioned gentleman, mounted on a sporting-looking chestnut, turns the corner.

"Talk of angels, sure to see them," says Oldwig. "Good morning to you, Richmond. How are you?"

"Well, not quite as well as I might be; rather a heavy dinner last night at the Green Dragon, where they proposed the Master's health too often. But no doubt a gallop after a good straight-necked fox will soon put me right. Anyway, Oldwig, I shall look to you to give me a lead to-day, as my nerves are a little shaken, and I know you never let them get far away."

Now, if there is one thing that Oldwig likes more than another it is a little soft solder. As a matter of fact, be it whispered, our friend is a bit of a funker, and a deal better across country after dinner, when the wine has been freely circulated, than at any other time. But this is only a detail.

By this time they have arrived at the meet, the rendezvous being an old-fashioned manor house, snugly nestling amongst high elm trees. The rooks, flying high, are quite in a commotion to-day, as they are unaccustomed to seeing so many red coats about, and fear for their safety.

The hounds are in a meadow in front of the house surrounded by a group of admiring bumpkins. The majority of the sportsmen are partaking of breakfast. Let us follow Goodbery and Oldwig, who have just dismounted and are about to enter the house. Within all is bustle and excitement. The kindly host, with beaming face, is cutting away at a great side of beef, assisted by half-a-dozen laughing maids who are further augmented by a couple of red-waistcoated servants (doubtless procured from the stable), for the strain on the establishment requires all the power available.

"How are you, Goodbery, my boy? Take a seat next to me," shouts the host, with the voice of one who is accustomed to speak to people out of doors. "Come, what will you take – rabbit-pie with forced-meat balls, cold chicken and tongue, pigeon-pie, or a bit of that loin of pork, fed on the premises, it's rare stuff to stick to your ribs, my lad."

Our friends do full justice to the meal, for it must be remembered that hunting in the time of which I am writing was different from the sport of to-day. In those days the fox was sometimes started before sunrise, and hunted 'till sundown, when the jovial huntsmen returned to their dinner, which they made the principal meal of the day.

Several farmers come in and are welcomed in the same boisterous manner, and after all have satisfied the inner man they mount their hunters again and take the field.

There is a good field to-day and a large attendance of regular followers.

What sport, I ask, is there to be equalled to that of fox-hunting, with its healthy exercise, change of scene, sociability, and excitement? Was it not Lord Palmerston who said the finest thing for the inside of a man was the outside of a horse? Personally, I don't think he was far wrong, I don't want to be sour, but very different is the hunting of the present day of which some young men think so much, from the sport of our grandfathers, in the days when railways were unheard of, and every face was known at a meet. Nowadays many people go out for the sake of pace and jumping fences rather than for love of the good old sport of fox-hunting. How many of our modern sportsmen know the name of one hound from another, or which are most reliable or throw their tongue in cover?

Imagine yourself living at the early part of the century, when our forefathers set out at daybreak with their friends and neighbouring squires, having heard of damage done to hen roosts; they would unkennel their hounds and try to get on the drag of the old fox, and slowly hunt up to where he was sleeping off the effects of his midnight feast. What hound work! What music from those old-fashioned, deep-throated packs! The huntsmen knew every hound and cheered them on by their names; many long runs they had, and surely it was better sport than running into a fox after twenty minutes, as with present day hounds, for very few foxes nowadays will stand up before them longer if there is a scent.

Talking about long runs reminds me of one that took place in 1793. Here it is, taken from a good old journal:-

"On the 11th January last an old dog fox was found in Perrin Wood in the County of Kent, by T. D. Brockman's hounds. He ran through the following parishes:- Postdene, Saltwood, Newington, Paddlesworth, Acrise, Limminge, Eltham, Denton, Barham, Kingstone, Bishopsbourne, Hard, and Bridge vStreet, forming a zig-zag of 32 miles, which was run in two hours and twenty-one minutes to the last-mentioned place, where the old dog fox was forced to surrender a life which he endeavoured to preserve by that strength and agility unequalled by his race."

Many of the packs in the early days were trencher fed, and on a hunting morning were collected by a man who went through the villages blowing a horn. I know an old man who still takes a keen interest in all matters connected with sport, although he has grown too old and feeble to do much himself When a boy he managed to persuade his father, rather against the latter's will, to keep a hound. One morning, when working in the forge, the old dog, who was lying on the floor, heard the sound of the horn in the distance.

"Father," said the boy, "shall I let Trueman out?"

"You go on with your work," was the father's reply, "and let the hound bide. It costs enough to fill his belly now without a' hunting."

Presently the horn sounded again, this time nearer. There was a crash and a sound of broken glass; the old hound had jumped through a lattice window.

"Blame it," said the father, "it would have been cheaper to let old Trueman a' gone a' hunting than a' kept him." Yes, times were different then. We now hear of the golden farmer and wonder what sort of a man he could have been. An innkeeper at Bagshot changed the name of his sign from Golden Farmer to Jolly Farmer to make it more comprehensible to the uninitiated. In the days of which I am writing, wheat fetched £40 a load, and a farmer could afford to send his corn to market with a team of six horses with good harness and bells. I once remarked to a present-day farmer what a good old custom it was to have bells on the horses, and asked him why he did not have them on his teams.

"Why, lor, sir," he replied, "I wouldn't do it for something. If my landlord saw me doing that, he'd think I was making a fortune, and would raise my rent at once."

So much for his landlord!

But I am digressing from my story. The hounds are now in cover, their merry music proclaiming the pleasure the exercise affords them. Dr. Viles, an impatient little man, rides up on his flea-bitten grey, with a lean head and neck, and asks the Squire if he thinks they will find in this spinney. He does not wait for an answer, but rides off to another corner of the cover, and asks a similar question of another sportsman, and again rides off before an answer can be returned. But his character is well known; there is no harm in him, and most of his friends know that no answer is required. He is an open-hearted little man, and many of his patients have heard him speak against medicine, although it is his calling. "What you want," he would say, "is plenty of horse exercise and a little dieting. Don't take too much medicine; it only wears out the stomach. When I first began to practise I used to be much fonder of prescribing draughts and pills than I am now. But as we grow older we grow wiser, and we begin to learn something when we get one leg in the grave."

By the silence in covert it is clear that there is a blank draw, so the hounds are taken off to Jobblin's Wood, about half a mile away. Here they are more fortunate, for almost as soon as they get into cover, they proclaim they have found their fox. Away tear the heavy weights, Goodbery and Oldwig included, for is it not half the battle to get well away? Crack goes the top rail as a blundering three-year-old gives the timid ones a chance. The hounds are running very keen on a strong scent, and although the field are not mounted on such mettle as is to be found in the highflying country of Leicestershire, yet they are on good, useful horses, made, perhaps, more for endurance than pace, and most of them safe conveyances into the bargain. "When you get over forty, however sporting you may be," Goodbery is fond of saying, "the less falls you have the better, although in my time I have had my share, and more, too, for the matter of that."

Up comes our host of the Manor House, mounted on a cocktailed bay, that looks a hunter all over, and worthy of the noble-looking man who bestrides him.

"I think they are making for Tilling's Wood," says he; "let us get on, or we shall lose the best part of it."

They cross a magnificent park, where sheep are grazing amongst the fine oak trees. The hounds run close up to the mansion, as though blaster Reynard had half a mind to stop and seek the kindly shelter of its portals. But no, away they stream across the grass, jump the park railings into the coach road to an open, breezy common, where they are at fault: but only for a moment, for hark! a leading hound owns to it. Jack, the huntsman, cheers them on, and they are again away in full cry. Goodbery, in moments like these, feels that he could stand up in his stirrups and shout at the top of his voice, so great is the pleasure and excitement of the chase. But no doubt had he done so, he would be taken for a lunatic, which, under the circumstances, would perhaps have been a reasonable verdict for any onlooker to have arrived at.

Crossing a few low-water meadows with a nice little brook, that heavy weights can all manage and chat over during their dinner, the sportsmen mount a steep hill. On arriving at the top, they find that the fox has run along the ridge till he has reached a large plantation, where he hopes to baffle his pursuers. The hounds, however, are bent on having his blood, they vow he shall die; but it is not all over yet, for having got his wind outside this plantation he makes another gallant bid for life by sinking the hill and crossing the country that lies below. Some heavy ploughs here have to be encountered which find out the weak places in the horses. Next comes a nice jump for a clever hunter, a bank with a ditch on the take-off and landing side, where a couple of horsemen bite the dust, but they are soon up again and seem more eager than ever to show it was only a mistake, and that they could do much bigger things and not come to grief.

Some of these little doubles are very tricky and need some doing. There was a good old sporting farmer in Hertfordshire who had one constructed on his farm so as to be seen from his dining room. In this way he often managed to have some good sport when the hounds were running in his neighbourhood. There were always two or three riders caught in the trap if the fox led them over it; indeed, our friend was often heard to declare that it furnished quite a diversion for his wife and daughters, who might otherwise have found the country monotonous during the dull and dreary winter months.

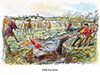

Every run must have an end; after crossing a couple of ploughed fields, Master Reynard turns round and gallantly faces the pack who shortly demolish him. Jack, the huntsman, is soon dismounted and, holding the fox aloft, he performs the obsequies, surrounded by the baying pack.

![]()

![]()